Between the 427 S/C and 289 slab side, both should be in your garage

As told by Glenn Stasky

Photos by Steve Temple

After a ride around Laguna Seca in a real 289 race Cobra many years ago, I caught the bug — or more aptly, the snakebite — twice, which lead to the pair of Cobra replicas I own today. While one boasts big-block power from the mighty 427 FE, the other is a featherweight 289 car, and people often wonder how the two compare. But first, here’s how it all happened.

A good friend of mine, Gordon Gimbel, is a longtime Cobra fanatic. He once owned a Cobra parts store and also campaigned a cutback-door, 289 USRRC Cobra (CSX2514) for many years in vintage races. I was lucky enough to ride in it at Laguna Seca around 1990, but this was long before safety rules prohibited passengers in single roll bar Cobras. It was a hair-raising experience to say the least.

We went into Turn 2 so fast that the car’s suspension compressed on the right side, and the tires were rubbing on the fenders. We hit over 130 mph and I did not have a windshield in front of my face. I remember my helmet being lifted off my head as we raced up the front straight. I also met Carroll Shelby that weekend, and I was hooked.

So I blame Gordon for my Cobra addiction, which lead to a pair of replicas in my life — one a 289 slab side and the other a 427 S/C. By the way, Gordon’s original 289 Cobra is now on permanent display at The Cobra Experience museum in Martinez, California.

Tracking Down a 427

Soon after, I started looking for the right Cobra replica to build and spent over a year inspecting various brands. It was while visiting ERA Replica Automobiles in Connecticut that I made my decision, as they really know what they’re doing and the pride of ownership was evident in every employee. I struck a deal with Peter Portante but was told I would have to wait about two years.

So, I spent this time searching for the parts I’d need, including a period-correct 427 FE big-block engine, as I really wanted to do this right. Luckily, I found one in a speedboat in town. The boat was a mess, so the owner sold me the engine and gave me the boat. The rest of the driveline came next, and I soon learned how to rebuild a Jaguar rear end and change the syncros in a Ford Toploader transmission. However Peter called me the following month and said that a customer had delayed his delivery for financial reasons, meaning he could ship my car next month — wow! That was some luck.

The car arrived, and I set about the build process. When the time came though, I elected to drive the car for a while before I started the bodywork. Also, my painter suggested letting the fiberglass fully cure before painting it. I ended up driving it in dull gel coat for a year since it took me that long to figure out what color paint to use.

I can say that not painting right away was one of the best decisions I made. I was able to sort out little details and adjust things without worrying about scratching the paint. I did a few track days, a few long-distance tours and just drove the heck out of it. With 5,000 miles on the clock, I had a good understanding of the car’s dynamics and limitations.

But eventually, the time had come to start the bodywork. After removing the drivetrain, I spent over 200 hours over the next six months handling the prep work. My neighbors likely shook their heads in disbelief when they saw me wet-sanding the car outside in the rain.

Selecting a paint color was harder than I thought, though, and I bought an old Mustang fender and painted it various shades of blue while trying to make a decision. I finally stumbled upon the exact color I wanted at a car show. It was a 1948 Hudson in banner blue.

Painting a car is an art, though, and I enlisted a friend and expert painter and for the job. When it came time to lay out the stripes, I noted that they’re actually not parallel. Peter Brock was a genius in how he designed them, as they give the illusion of being straight, even when they stretch over the compound curves of a 427 body.

When the car was painted, we rolled it outside in the sun and noted that banner blue is indeed a great color for a Cobra. One week later, we had the entire car put back together and off I went for a drive. I am sure the car is even faster with a smooth coat of paint, right?

The car is no trailer queen, as it has seen many miles and even a few track days. When it was completed, there were not many Cobra replicas around, and it really drew attention wherever it went.

Bagging a 289 Slab Side

After seeing a number of 289 slab-side Cobras over the years, I became interested in acquiring one, but they’re much harder to find than the big-block replica I bagged roughly 20 years earlier. I searched and searched and even called my Cobra friends to see what might be available. Finally, I found a Hawk 289 in New York near where I grew up.

The car was originally built in England by Gerry Hawkridge of Hawk Cars. At the time, it was one of only four Hawk 289 cars in the states. After making a deal, I had it shipped to my home in California.

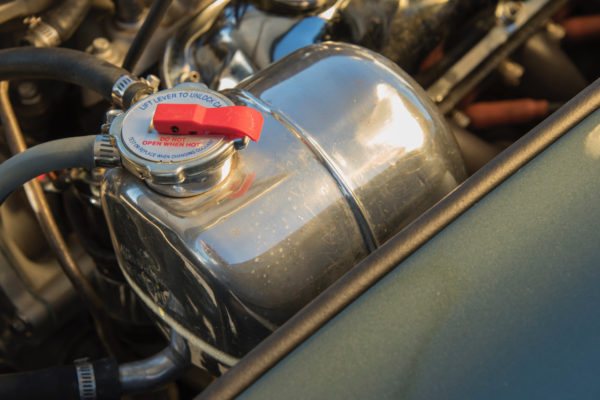

I found that the car had some really “cool” patina when it arrived, but it was a bit rough underneath. Upon closer inspection, the patina hid some insidious rust, and one side frame tube was rusted through! The car had been neglected as it was parked near the ocean in a beach town on Long Island. Over 20 years of use had taken its toll, so I decided to fully restore the car. I’m not known to take shortcuts, and this would be no exception. Engine, transmission, differential, suspension, wheels, brakes, interior and plumbing were all disassembled and renewed. Gerry at Hawk was very helpful in sourcing and offering restoration advice. But, as a total restoration is even harder than a new build, I decided to enlist some help. Luckily, my local area has an abundance of excellent automotive fabricators and suppliers.

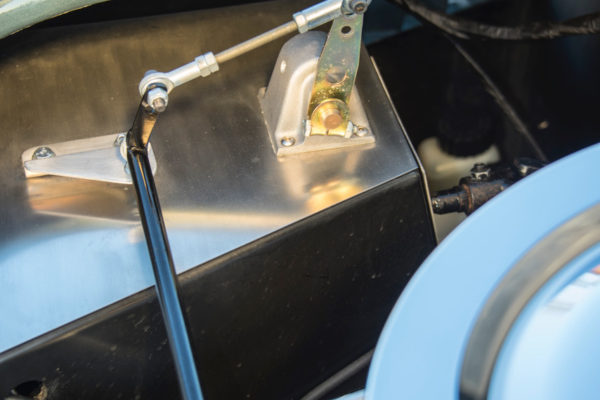

The frame was stripped and sand-blasted to reveal the damaged tubes. After jigging the frame securely in place, the offending tubes were cut and replaced. My welder is an ace roll-cage fabricator and has built many tube-frame race cars, so fixing two rusted tubes was not difficult. He even copied the welding “style” of the Hawk fabricator so that no one would ever know the part was replaced. Once powder-coated (in a very original-looking satin black), the frame looked as good as new.

Even though I rebuilt my first Jag differential, I decided to have a pro do the work this time around. I had heard of a Jaguar XK restoration shop right in my town, and when I went there, I saw a raw aluminum AC body! It was not a Cobra, but an original Ruddspeed AC — one of 26. The rest of the garage was filled with Jaguars and odd British cars, and I determined this would be the perfect place.

My car also came with Austin Princess calipers and Peugeot 505 rotors, which are difficult to find, let alone anyone who has even heard of them here in the states. A little research led me to a caliper restoration business in Chicago. These calipers are very similar to a Range Rover caliper, so pistons and seals were not terribly difficult to source. Once the years of rust were stripped off and the calipers were replated, they looked brand new again.

The rotors were a different story, however, as the 505 was never really imported here, and spares are nonexistent. Some research led me to a Mazda Miata rotor from 2001. A bit of machining and we were in business.

The car was originally painted a light metallic green used on a Ford Taurus, but I wanted a richer-looking color, one that mimicked an early Aston Martin race car. After numerous test panels, I stumbled upon a Porsche green that was only available for two years. And as long as you don’t live within 100 miles of my house, you can use this color on your car, too.

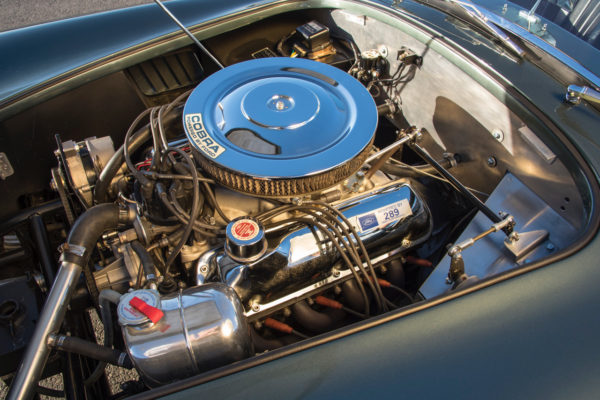

The original 289 in the car was said to be a Hi-Po version, but it was not, and various odd noises and mismatched parts dictated a complete overhaul. We went with a modest cam grind and a slight bump in compression. A better intake manifold with porting, a new carburetor and balancing put us ahead of the original Hi-Po performance, delivering about 275-plus horses.

My engine builder Cole Cutler is an old-time Ford man who has a few Bonneville records to his name, so my little Sunday runabout was in his wheelhouse. I was lucky to buy the correct water pump and cover, as early year blocks had the water outlet on the other side. Finding the correct valve covers, air cleaner and proper Cobra decals was a snap.

My car originally came with MG front suspension with oldschool lever-arm dampers. I wanted an upgrade, and again Gerry came to the rescue. His custom-designed coilover conversion kit is absolutely superb. The car drives beautifully, and the steering turn in is direct and much more precise. The car now drives like it should have from the beginning. When the original T5 was overhauled and checked for wear, we found that the wrong lubricant was used. This T5 is what is called a World Class unit, which uses carbon fiber plates and must be filled with ATF instead of 90-weight oil. It would have been a short matter of time before the oil would have ruined the transmission. Luckily there is a huge transmission repair facility around the corner from my shop, and this T5 was a snap for them compared to, say, a Tiptronic Porsche transmission.

The original build used many solderless crimp connectors behind the dash, and not only were these ugly, but some of them were incorrectly crimped. So each and every crimp was redone with crimping, soldering and shrink tube. My business does highend wiring on off-road vehicles and motorcycles, and clean wiring is our stock in trade. I even made the whole dash removable with a multicontact connector.

Finished off with a correct-looking voltage regulator and period spark plug wires, the 289 was finally ready for its reintroduction to the road. The first drive was like magic, and I felt like I was a time traveler going back to the early days of the Cobra roadster.

Cobra Conclusions

So which car do I like driving the most? That is easy — the one I am sitting in! Each has its own merits and uses. You could liken them to female dancers, as one is a ballerina and the other hails from the Vegas strip. (You figure out which is which.)

The 427 can be brutal, and it’s quite loud. But the car is still comfortable, the steering is precise and the throttle is progressive, up to a point. When the secondary barrels of the carburetor open up, you better be holding on and have the car pointed straight ahead. It can spin the tires on a third-forth upshift, yet you can drive it around town with ease.

It is nearly impossible to drive anywhere unnoticed, and everyone will hear you coming down the street. The ERA has a good ride and even handles well on a racecourse. It is a very fast track car that gives up little to race-prepped cars. It has seen track time at Laguna Seca, Thunderhill and Sonoma Raceway.

As for comparison, there’s really no substitute for cubic inches. The 427 wins in every contest except fuel mileage. The 289 has a fifth gear overdrive so mileage is of course better, but neither car is designed for daily commuting anyway, so who cares? From a roll, the 427 walks away in any gear. It’s a torque monster. The 289 is less forgiving about what gear you’re in.

Even so, the 289 is certainly special as it never fails to draw attention at a car show. It is just so different. The 289 is the car you drive when you want to go out to a nice dinner, the 427 is the car when you are in the mood for a good, juicy burger. The 289 is not nearly as fast or loud, but it offers a bit of elegance that brings you back to the ’60s. What’s my decision? There should be two Cobras in every garage.

Comments for: A Tale of Two Cobras

comments powered by Disqus