Cobra Coupe or Roadster Replica

Text and Photos by Steve Temple

Decisions, decisions. When mulling over choosing a Cobra, it comes down to two basic types: the more recognizable open-cockpit version or the competition-derived Daytona coupe. Within the former category, there are several models: 289 street, 289 racer, or the mac-daddy 427 S/C (and there was a street version of the 427 as well, but rarely seen in replica form).

As for the coupe, only six of the originals were ever built, so there’s not as much variation with this model. It was specifically designed for racing against the Ferrari 250 GTO. That’s because, as Carroll Shelby used to complain, “The roadster had the aerodynamics of a shoebox.”

As proof, on the long Mulsanne Straight at Le Mans, the roadster topped out at 157 mph, some 30 mph less than the Ferrari 250 GTO. This difference in speed resulted in a shortfall of at least 10 seconds per lap, wiping out any power and acceleration advantages that the Cobra had in the slower sections.

Shelby asked designer Pete Brock to come up with a shape that would slice through the air. While an aerodynamics consultant from Convair said the tail needed to be three feet longer, Brock overcame wind resistance by employing a Kammback configuration — basically a tapered shape with a recessed area that reduced turbulence off the back end. German aerodynamicist Wunibald Kamm is credited with this design element that calls for a body with smooth contours that continues to a tail that is abruptly cut off. The shape reduces the drag of the vehicle, so much so that during initial testing of the prototype, the Daytona Coupe hit speeds of 190 mph at Riverside Raceway. Brock’s slippery shape proved out in competition, as the car took home the FIA World Sportscar Championship in 1965. Heady stuff back in the day, and it still resonates with Cobra fans the world over.

Which brings us to two Cobra enthusiasts in particular, Mario Abril and John Saia. Both cars are replicas made by Factory Five Racing, but that’s where the similarities end and the differences begin. We’ll provide profiles on each of them and their involvement with their Cobras, with telling indicators as to what drove them to make their choices. While their reasons probably won’t sway opinions one way or the other, they can clarify a potential selection for prospective Cobra owners. And current Cobra owners might pick up a technical pointer or two on the care and feeding of their Cobras.

Roadster Recollections

For Mario, his fascination with Cobras was cemented by a chance encounter with entertainer and car collector Jay Leno. “Though I had seen Cobras in magazines, I’d never seen one up close,” Mario recalls. “Until once while bicycling at the Rose Bowl, Jay Leno came cruising by in his. I stood there with my mouth agape. From then on it was my dream car.”

How that formative experience turned into a reality for him required nearly four years of buildup time. While he had never built a Cobra before, “I’ve always been a gearhead working on every car I’ve owned,” he says. “I worked as a mechanic apprentice at a Texaco in Tennessee for a couple years, and had a year of formal mechanics training at Chattanooga Tech.”

Armed with these hard-earned skills, Mario spent untold hours learning from other car builders on the forum, www.ffcars.com. “It was invaluable for my build,” he acknowledges. All of the parts he used are new, and a friend with access to a large sheet metal shop helped him manufacture custom aluminum panels to improve the fit, plus add features. These include a CAD-designed competition dash with glovebox.

“My daughter is a Stanford engineering student and used CAD to help me design roll bar trim rings and block-off plates that were then cut at a local water jet shop,” he adds. “She also made my emergency brake handle at the Stanford machine shop.”

Sometimes it takes a village to build a Cobra, as Mario cites the contributions of many friends and firms, especially two local shops: Ace Torrance Industrial Hardware and Torrance Electronics. The hardware outlet has every conceivable fastener on hand and allowed him to upgrade all included fasteners to the highest quality and finish, so he visited this store regularly throughout his build. Also, Torrance Electronics provided a plethora of electrical components. Although just a hole-in-the-wall type of shop, it’s crammed with every component. “If these shops hadn’t been in close proximity,” Mario points out, “I’m not sure I’d have been patient enough to wait for improved parts from the Internet.”

Assembly started by removing the body from the chassis and placing it on a rolling body buck for storage. Then all of the temporarily attached aluminum panels were photo cataloged and removed for later finishing and reinstallation.

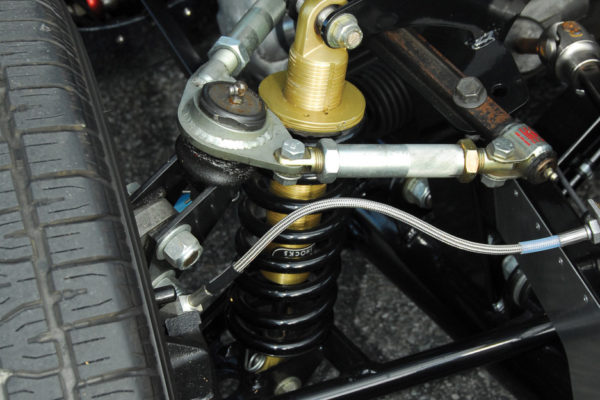

The suspension went on next. Mario customized the front lower control arms for smoother operation using high-deflection rod ends. All rear suspension rubber bushings were replaced with Whitby Motorcar’s captured spherical bearings for a smoother, more precise operation. Vintage Performance Motorcars provided the front anti-sway bar and he worked with this company to design an improved design for the IRS sway bar.

As for the driveline, Forte’s Parts provided driveline components: a Ford Racing aluminum housing, 31-spline Torsen differential, Forte’s solid diff mounts, 3.27 gears, and The Drive Shaft Shop’s 800 hp axles. For brakes, Wilwood supplied six-piston calipers with 13-inch rotors up front, and four-piston calipers with 12.5-inch rotors in the rear. A custom bracket was fabricated to accommodate IPSCO emergency brake calipers, a considerable upgrade. All brake lines were custom-bent, stainless hard lines and braided stainless flexible lines from AN Plumbing. Emergency brake cables were routed via custom pulleys and brackets for a more secure installation. The cables themselves were custom made by VER Sales in Burbank, Calif. Reservoirs are from Kirkham on custom aluminum brackets.

As for the fuel system, all hard lines are custom-bent stainless with lines and fittings from Swagelok, using a 1⁄2-inch input and a 3/8-inch return lines. Flexible lines are custom stainless braided Ultraflex Teflon lined, also from AN Plumbing. The fuel pump is an in-tank unit from High Flow Fuel on a custom hanger to accommodate AN -8 and -6 attachment points.

Instead of using the included Factory Five electrical system, Mario installed an Infinitybox computerized electrical system. “Being an IT guy, the computer aspect of this system really attracted me,” he explains. “This required custom wiring the entire chassis myself. It also allowed me to design the system as cleanly as possible to avoid excess wiring cluttering up the engine bay.” Also, due to the relatively low amperage requirements at the switches, he felt comfortable using genuine Lucas switches, which he prefers the look of, and overall gives an improved setup.

While many of the above components were being installed, Mario prepped and fabricated aluminum panels for the foot boxes and interior, which required meticulous adjustments with a grinder, file, sander and occasional hammer. Panels facing the engine bay were powder coated, while all other panels were treated with Alodine (common in aircraft applications) to prevent corrosion. Upon final installation all panel seams were bonded with Bostik 1100 FS. This urethane adhesive ensured a tight seal in the cockpit against water or hot air incursion. “In case I got caught in the rain, I drilled and plugged two drains in the cockpit floors to let water back out,” he relates.

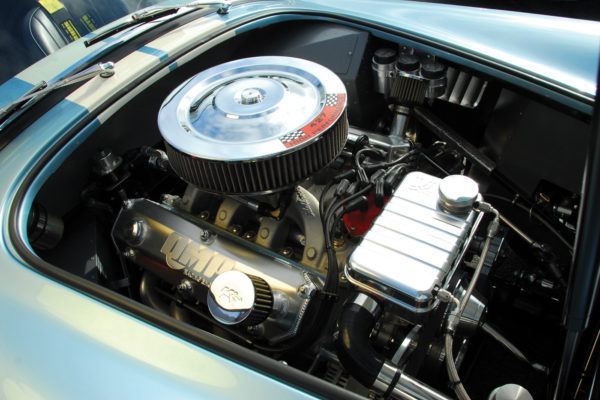

Getting to the heart of the matter under the hood, Mario initially wanted to build the engine, but realized that he didn’t have the necessary tools to do it to the desired spec. After some research, he had QMP Racing in Chatsworth, Calif. build him a 427 ci stroker with a Dart SHP block and Dart Pro 1 CNC heads, plus a SCAT-forged rotating assembly. Actuating the valvetrain is a Comp Cams custom grind cam, rockers, lifters, and springs. Edelbrock provided the water pump and RPM Air Gap manifold. Topping the whole assembly is a Holley Ultra HP 750 carb with a spacer from Unleashed Custom Machining. Supplying juice to the plugs is MSD’s distributor, coil, and Digital 6AL.

All told, final engine dyno was 570 hp and 556 lb-ft of torque. This load of power funnels through an upgraded TKO600RR from Liberty’s High Performance with mid-shifter by Pro 5.0. Clutch is a RAM Powergrip. Once the engine was in, Mario was able to focus on headers. Stainless Headers sent him its jig so he could get the company to make him a custom set of headers. “I built a jig to bolt to the chassis to hold the side pipes exactly where I wanted them,” he explains. “Then I adjusted the Stainless Header jig to match exactly. Those guys do amazing work. The finished headers were perfect.”

With all the mechanicals in place Mario was able to finish riveting all panels and start insulating the interior using EZ Cool insulation, and Thermo-Tec reflective insulation adjacent to headers on the foot boxes. The result is zero heat incursion.

Paint and body were performed by Miller Customs in Temecula, Calif. “This shop has done more of these cars than anyone and does terrific work,” Mario attests. After some consultation they settled on a custom color based on 1967 Ford Silver Blue with Wimbledon white stripes. Apparently the silver blue color was very difficult to paint but the results came out great.

Looking back on all the wrenching Mario had to do left him with a solid sense of satisfaction. “Building my own Cobra gives me a different familiarity with it,” he notes. “With a couple exceptions I’ve turned every nut and bolt on the car. When I walk around it to admire it I frequently end up doing mechanical checks. I don’t even think of it as a whole. Subconsciously I almost just see an exploded parts-view of the car. I can visualize every part clearly in my head and it can be a distraction from the whole.” Except when he’s driving it.

“It is almost a cliché in the Cobra community to say the driving experience is visceral,” he admits. “But that is the best description. There is very little between me and the road except a few bits of metal and a whole lot of horsepower. In traffic it feels barely contained. If an opening appears the Cobra takes it almost of its own volition, with the exhaust loudly proclaiming ownership. I’ve driven cars that are as fast but none that directly impart as much of the driving experience.” An awesome way to take command of the road!

Coupe Compulsion

John Saia’s Shelby “disease” started in 1963 when he had a startling experience, similar in intensity to Mario’s.

“I saw a Cobra compete in the Hershey Hillclimb in Hershey, Pennsylvania,” he recalls. “I was still in high school. It sure sounded different than anything on the hill that weekend. And, it sure was fast! That was the initial moment when it struck. Each fall in October I’d watch the Hillclimb, I’d always look for and root for the

Cobras.” But these were roadsters, and he later acquired a Shelby GT350 Mustang, so how did he develop a compulsion for a coupe?

“It wasn’t just Shelbys,” he continues. “It was also Cobras, Daytona Cobra Coupes, and it was Carroll Shelby himself. In those days right up to today, I’ve been enamored with the cars, the results of Shelby American, and with ‘The Man’ himself.” In between his first ’66 Shelby (#336) and his second ’66 Shelby (#2060), there was this dream of owning a Cobra. “I missed a used 427 Cobra circa 1969 for $7,000 — unaffordable on Army pay!”

But the more John watched Shelby American and Carroll Shelby over those early years, he began to lock on to the Daytona Cobra Coupe, primarily because of the unique beauty of its shape and racing successes.

“I still had a thing for Cobra roadsters, but as time went on the Daytona kept grinding on me.” He isn’t the first — nor the last — to be captivated by the coupe’s alluring lines.

“In the mid-2000s, I had the opportunity to speak personally on the phone with Pete Brock about Factory Five and Superformance Daytonas,” he recalls. “Pete was very patient with me and gladly offered his expertise on helping me to shape my decisions. In 2012, as I approached retirement age, I began to realize two things: I could afford a Daytona, perhaps a Superformance or an FFR; and I had nowhere to build one.”

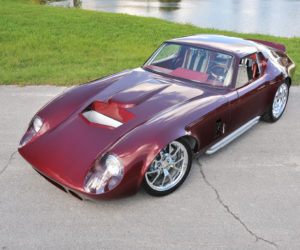

That’s when John began to search in earnest for a completed coupe. “I saw many of both flavors. None were appealing…well, until I saw the Daytona I now own. This FFR Daytona was built period-correct with all-new components (no donor parts).”

It’s Guardsman Blue with Wimbledon White LeMans stripes. This Coupe was originally built for a New York State Supreme Court judge by Andy Schaefer in Quogue, Long Island, New York. It passed from the judge, to the judge’s estate, back to Andy, then to John in Southern California, who’s owned it now for nearly two years.

So what’s it like to own, sort, maintain and drive a Daytona Cobra Coupe? “Because the Daytona is so unique (and rare), ownership is a delight,” John says. “It’s a very special, iconic car because of its history, shape, and individuality. It really does get attention everywhere it goes: shows, just driving, on the road or sitting still.”

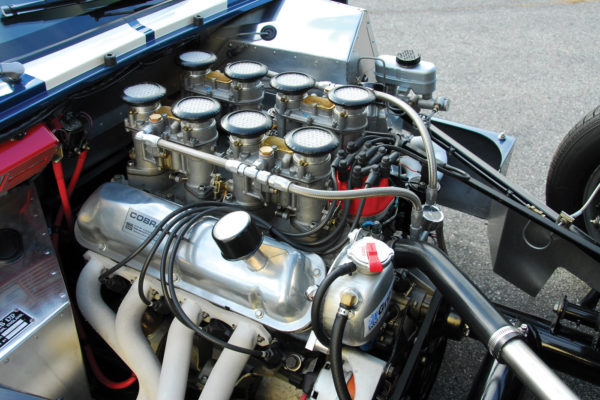

This engine is based on a Ford 351 Windsor, and is a 392 Ford Motorsports crate motor. That means it’s been bored .030 over for a 4.030-inch bore and stroked to 3.850 inches from 3.50, with forged pistons and forged steel connecting rods, and a steel crankshaft. The heads are Ford Racing GT40 aluminum cylinder heads. The camshaft is a hydraulic roller cam along with roller rockers, and a nominal lift of .570” lift and 236° duration at 0.050” lift. The fuel cell, electric fuel pump and regulator provide sufficient volume at 2.5 psi to feed four 48-IDA Webers, mounted atop an aluminum intake. Spark is provided via an MSD ignition box and shared among cylinders by a billet MSD distributor. On the downstream side, there are steel tube headers and four-into-two mufflers on each side, all coated in VHT white.

Here’s what comes out: a genuine 435 hp on tap, along with roughly 500 lb-ft of torque. Redline is set at 6,000 rpm, and it will pull all the way there (and over!). All that power goes through a Tremec T-56 five-speed to a Thunderbird Super Coupe IRS 3.42 differential which then spins huge 295/50R15 rear tires mounted on 9.5 x 15” knock-off wheels.

Yes, sorting has taken some time. “I’m a perfectionist, so I’ve had to be patient to get the Daytona, in my view, perfect,” he admits. When he first took possession, “The Coupe had gone largely unused for long periods. There were hydraulic clutch problems, Weber problems, suspension noise problems, etc. So I focused my attention on each area, one at a time.”

John admits that he even created some new problems in the process: like when, for no good reason, the trans completely spit out the tail shaft bushing and began a ferocious trans leak. He powered through that fix and others, such as an originally undiscovered heavy float in one of the Webers. That kept him chasing an overly rich condition for a few days. But once tweaked and solved, the Webers (and John) are now happy campers.

Street driveability is superb. “Don’t believe those who say you can’t get good street performance with Webers,” he advises. The hydraulic clutch was mostly a nasty brake-fluid issue which was resolved with a thorough flushing and ongoing use. “Sorting takes time, but in the end it’s well worth the effort,” John says. “At the same time, I now know the Daytona very well, I fully trust the car, and now I intimately understand its characteristics.” Words to the wise, as they say.

“Maintaining is actually the fun part,” John says. “I find solace in cleaning, polishing where appropriate, and prepping for shows. For example, I especially like safety wiring the knock-off spinners whenever I need to R&R the wheels.”

It’s not all spit and polish, however. Sometimes it’s changing the oil, bleeding the brakes, checking and adjusting air pressure, getting an alignment and the tires balanced, or replacing an oil temperature sender. It’s easy to keep after and always ready to show or drive. All in a day’s work when you use a Daytona Cobra Coupe as intended: driving!

Summing up, “This is where the rubber really does meet the road!” John enthuses. “This is what it’s for. The Daytona Cobra Coupe gets weekly doses of fresh air, sunshine, and high-test gas. It’s effortless to drive, smooth, and really fast. There’s plenty of horsepower, and oh, how the Webers generate torque!”

He adds that it’s surprisingly quiet at idle, but whenever it’s pulling hard the Daytona is ungodly loud — in a really good way. The steering is quick and light, handling is neutral with some throttle oversteer (oh what fun that is!). Since the Coupe is largely period correct, however, amenities are virtually nonexistent. No air conditioning, no side windows, no insulation whatsoever, no stereo surround sound (except for the exhaust pipes about 30 inches from your ear!). It’s mellifluous, thrilling, powerful, and the ride of a lifetime!

Comments for: Coupe or Roadster

comments powered by Disqus